5 February 2016

Bees are an exception to the rule saying that biodiversity is highest in the tropics. This is not true for bees – the climate in the tropics is not favourable for the flowers they forage on. In tropical areas you find other pollinators – like bats or birds – much more often than bees. Hotspots for bees are regions with mediterranean climate: except the Mediterranen basin these are Central Asia, Southern Australia, the Cape region, the US west coast and – Chile. Yes, the land of giant bumblebees. Though, where the bumblebees are, the climate is not really mediterranean. More cool and rainy. That is because bumblebees are another exception from the rule: bees in general like it warm and dry. Bumblebees though do not, they have an integrated heating pump and therefore can go further north or south than other bees. Bombus dahlbomii, is not only the world’s biggest bumblebee, it is also distributed much more southwards than other bees. On the photo above you can see an area which is still populated by these giant pollinators: the valley of Río Francés in the Torres del Paine Natural Park. I was there in January 2005 – southern hemisphere summer, but the temperatures did not feel like it. Ideal conditions for Chile’s native bumblebee though and fortunately in this region they are still present and impress all the tourists that go hiking in this really amazing landscape.

Natural Park Torres del Paine, Lago Skottsberg

In Concepción though, where I started my story with B. dahlbomii many years earlier, it almost disappeared. The campus of the university was full of them, as well as the hills around the city. Concepción is already much more north than Torres del Paine, with moderate climate – still suitable for those who like it cool. By the way, pay attention at what time of the day you see bumblebees. In summer, you will not see them in at noon until the later afternoon when it cools down again. If you want to know more about how bumblebees live and regulate temperature, I strongly recommend Bernd Heinrich’s book “Bumblebee economy”.

Bee diversity hotspot

In Concepción not only I got in touch with B. dahlbomii, it was also the place where I got aware about the enormous variety of bees. There is a big entomological collection at the university, with many specimens of bees. I liked to just watch all these strange animals and it definitely trained my eye for habitus – very useful in the field. My work though was not very systematic, just an additional interest of all these adventures in that year.

Chile is a very long (4275 km) and narrow (an average of 180 km) country with many different climates. Only crossing the coastal mountains from Concepción to the Central Valley the climate is much warmer and dryer – very good for the wine production. In these mediterranean areas 183 species have been described, further in the north, in the deserts another 176 species. In total in Chile there are 426 species from latest countings. This may not seem so much to call it a hotspot, but consider that Chile is an “island”. Not in the classical definition, of course, but geographically isolated by Atacama desert, Andes, Pacific ocean and Antarctic in the South. A characteristic of isolated areas is a low number of species but there can be a high proportion of endemic species. Which is true for Chile. If not the European had brought honeybees and other animals and plants that are a threat for this susceptible balance.

Echium meadow, an alien plant in Chile

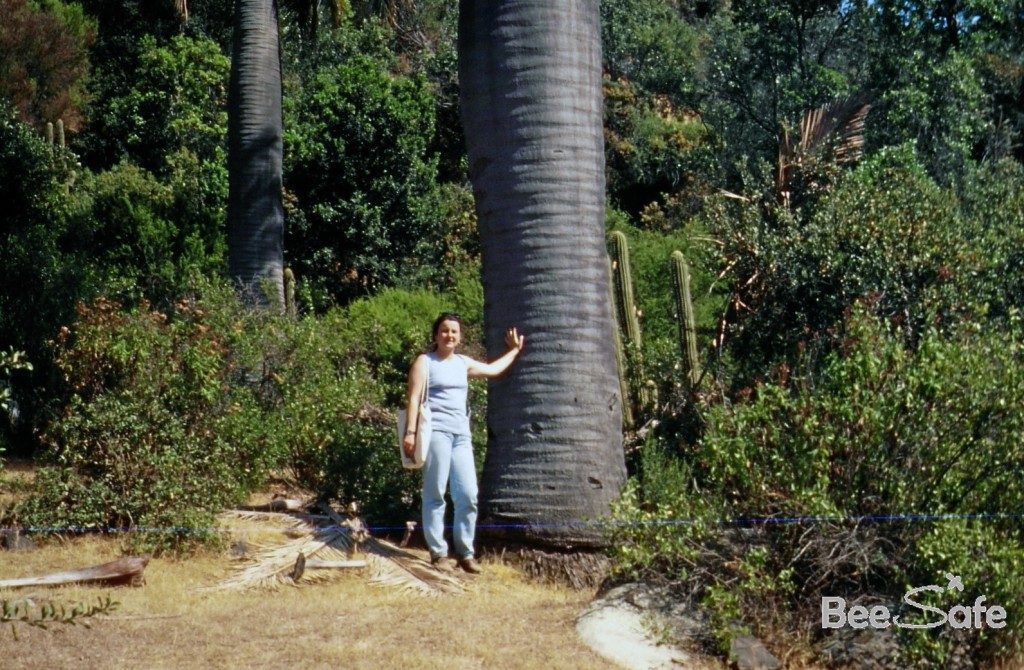

This picture may seem idyllic, but it is not. It is somewhere travelling up into the Andes starting from Los Angeles (Chile, not US), but I do not remember where exactly. With two friends, we were having an excursion seeking for aquatic beetles for one of these friends PhD thesis. When I saw so many flowers, I wanted to apply my new knowledge but was disappointed: alien plant (Echium sp.) and only alien bees, i.e. honeybees. None of those which make this country a hotspot for bee diversity. I did not travel so much into the North, where the diversity is higher. Only once with two friends from Germany in Chilean winter and once for the Entomological Conference in Valparaiso. At this occasion at least I had the chance to know Chilean wine palms (Jubaea chilensis), another endemic and threatened species.

Standing under a Chilean wine palm

It happens quite often that I would like to repeat some of these experiences I made as a student now, with the background and knowledge of 20 years more. I was too young to know in that times. How much I miss them.

0